The Other River

December 30, 2023

“From here we’ll have to leave the River,” Juan de Ayolas might have said from this spot nearly 500 years ago. And he might have said it with a sigh, suspecting what would come next: a brutal trek across the huge, hot, green-arid, dense-thorn-tree flats of South America now known as the Chaco.

The river had been curvy; its flow had been against them. But it had been an easily discernable and life-supporting path for the previous thousand and a half miles, and had gotten Ayolas and his men deep into the heart of this unknown continent. A heart that remains, to this day, unknown.

Too bad it wasn’t leading them in the correct direction! Stubbornly, the River kept flowing from the north, and what Ayolas wanted, what he needed, was for it to lead west, towards the legendary-rumored mineral riches of El Dorado, or perhaps the City of Caesars (either would be fine).

The River in question does not begin with an ‘A’. It starts with a ‘P’, as in Paraguay, and all-told it is damn near as long, in terms of navigable length, as that famous A-river of South America, if you include the downstream portions named otherwise that it merges with before reaching the sea.

The place we were stopped at is called Fuerte Olimpo these days, but in the past it was Fuerte Borbon…and quite possibly, if it isn’t in the exact spot, then at least it’s in the vicinity of where Ayolas established Fuerte Candelaria on said feast day in 1537. Here, Ayolas left his lieutenant, Domingo de Irala, in charge, told him to wait for four months (or maybe he said six), and, with 130 men and twice as many Paraguás, began the long, very warm, potable-waterless bushwhack across the densely thorn-shrubbed Chaco towards the Andes.

We never heard from Ayolas again. Lost, he became, in the vast interior.

I’d been tracking him along the River for two full days and two full nights by the time we reached this point. The thanks (or blame?) for this goes to Margaret Hebblethwaite, British author of the Bradt Guide to Paraguay, who also happens to be my boss’s boss.

If you do not want to pay for a flight, she writes, but want to be a pioneer in exploring the Paraguayan Pantanal…then take your first-aid kit, insect repellent, sun hat, camera, and a very long novel, and board the Aquidabán, which leaves Concepción on Tuesday at 11:00.

How could I refuse? “Oh Margaret, look what you made me do,” I said to myself now—not for the first time or for the first reason—with a grin and a laugh, from my hammock-home on the Aquidabán’s fore-deck, sweat dripping down my face, as I watched men unload stuff onto the riverbank. It’s thanks to Margaret’s eccentricities that I’m living in Paraguay in the first place.

Unlike Ayolas, I’d keep to the River, for now.

As for Ayolas, and what happened next, little can be known. Rumor has it he made it to the foothills of the Andes, got some silver, and got murdered somewhere along the way back to, or maybe even at, a by-then-abandoned Candelaria. Lieutenant Irala waited the agreed-upon time, and thereturned downriver to take charge of the newly established fort at Asunción. This was a time when it was very much hoped-for that Asunción would be THE strategic control point leading to Peru and all of its silver and gold.

When, amidst political struggles, Irala became temporarily demoted to “field master,” he made attempts to find Ayolas. He also crossed the Chaco himself and reached upper Peru, only to find that other Spaniards had arrived from the Pacific and grabbed everything a decade earlier (communications via the queen must have been rather slow in those days). Thus it became abundantly clear that Asunción would never be the gateway to the silver mines of Potosí, or to anything else.

Aw crap, they must have thought.

What do we do now?

After that, the only Paraguayan resource left to really exploit was its people, and this was done in due course. Nowadays it’s massive deforestation, both east and west of the River, in the (barely existing anymore) Atlantic Forest and Chaco respectively, for beef and soy export, that is key to economic output.

Regardless, the upper Paraguay remains a very remote backwater.

A backwater on which I had another full day and night left to travel on, watching the riverbank mesmerizingly, ceaselessly flow past my hammock.

By noontime on Friday, the Aquidabán reached its terminus at Bahía Negra, population maybe a thousand, near the point where the three countries of Brazil and Bolivia and Paraguay come together. From here, one bus a week is currently running a dust track through the Chaco southwestward (and this was good news; during rainy season which has now started, there are months where no bus goes at all). The bus left the following morning, in fact. “Go look for Myrta,” a boat crewman advised me. “Near the plaza. She does the tickets.”

I found Myrta, booked a seat, and walked through empty dust lanes in 103 degrees and full humidity, searching for a place to stay. Someone pointed me to an unlabeled, long low cement building near the riverbank. Another person, after I searched around for her, gave me a room and a smile.

I got the room cool with air conditioning as blue walls and warm dry sheets radiated latent heat. And in this manner, to borrow words from Joni Mitchell:

“I pulled into the (Perseverança) Motel to shower off the dust, and I slept on the strange pillows of my wanderlust.”

A Distinct Vintage

December 10, 2023

It’s going to be a distinct vintage without Pete.

So wrote Javier recently, my friend and boss at the Chilean bodega (winery) where I lovingly toiled the past two winemaking seasons. I had written to inform him I wouldn’t make it back for my third go in 2024. Maybe the following year, though!

Maybe 2025, yes, he replied. Tell me again what you’re doing in Paraguay?

Later, as I whiled away the afternoon in the deep backyard of my haunted cottage in Santa María, as December’s slanting summer sun pulsed in opulent trees amid a chorus of birdsong, I thought about what he said.

“A distinct vintage.”

As 2023 winds down, I hope you can see it as such. I’d love to know your stories.

It’s been distinct for me. It began in January in a foot of fresh snow atop the Carpathian Mountains (on the border between Poland and Slovakia) with the love of my life, Dewey Tran. Then he headed off to the Peace Corps in Thailand, and I went south to take up the Chilean bodega challenge a second time. But before reporting for work in Caliboro, you can be sure I trekked those summer south Andes once again!

The bodega nearly did me in to be honest with you. Not that it will stop me from going back; it’s just that work there requires strength and stamina. When the winemaking ended and the May-autumn matured and chilled, I hobbled north. But soon I was aloft over the Pacific, to Thailand to visit Dewey—an adventure in itself.

Then came Paraguay, this whole new situation. Learning to be a teacher again has been daunting but on balance invigorating. It’s hard to describe the feeling of energy mixed with a certain degree of terror I’ve experienced most afternoons these past five months, on hearing 22 exuberant ten-year-olds come sprinting around the corner of our school building and into our back garden quincho for class. Or later, while preparing for the social-intellectual challenge of an evening group of seven cynical, cheeky teens.

But even the teens (especially the teens) have been a joy. I am deeply honored to be subjected to this. I know I’m lucky, and thoroughly appreciate everyone I’m having the privilege to be with and know. Distinct, indeed! And as always, being a teacher, it is me who learns the most—by far and totally. Not to mention relearn. Recently I dusted off my chemistry text and gave a lecture on acids and bases at our food technology college across the street. It was reminiscent of my Peace Corps days in Ghana!—except this time in Spanish.

Now this year—this vintage 2023—is coming to an end. Sometimes I’ve felt the urge to bottle it up, put it on a shelf, and leave it there to age and ripen.

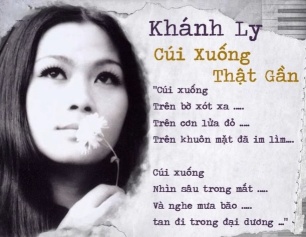

And then Dewey told me the story of Khán Ly.

In a turbulent and potent time, from the later 1960s up to the fall of Saigon in 1975, Khánh Ly sang the songs written by her soulmate, Trinh Công Son. Together they created a body of work embodying the soul of pre-1975 South Vietnam, and performed it live from Hue to Cà Mau, Da Lat to Nha Trang. Their songs came in three main themes: (1) Love, (2) Self (a broad topic; anything about the self and its storytelling), and, (3) the Vietnamese as a people and a nation.

Now at age 78, in her backyard in Cerrito, California, Khánh Ly sometimes takes off her shoes and gets up on a little private stage she has erected there.

This is to commemorate the very first night she and Trinh decided to go in front of people. It was at the University of Literature in Saigon, on a simple stage erected outdoors. Acoustic only; nothing was plugged in. But it was monumental for Khánh Ly even though she was already a seasoned performer.

As she stood in her áo dài and heels and prepared to sing, nervousness overcame her. She teetered, to the extent that she had to take off her shoes. This wasn’t enough. To steady herself, she had to go and place a hand on Trinh’s shoulder.

“Stand on your own,” he said, gently, brushing her off as the crowd looked on. “Sing from your heart.”

She did. And their legacy was born. From that moment on she was the Barefoot Queen. Trinh had chosen her because he wanted her to not just sing, but to tell the stories of a generation. And for legions that’s what she did. Her voice was not just singing—it was, and is, way more. Through music it is the audiobook of Vietnamese history, the souls and selves of its people, and a map of the human heart.

She and Trinh continued until the fall of Saigon in 1975. Interestingly, they never fell in love. This was a big mystery few if any understood. They were each other’s one and only aligned souls during that time, the best of friends. After the fall, he stayed on and eventually wrote communist propaganda music for Ho Chi Minh. She tried to remain, but as a true patriot of the South, she soon had to join a boat and flee as a refugee. Luckily, she survived.

In a recent interview, Khánh Ly said she built that little stage in her California backyard for the memory of that night at the University of Literature in Saigon, and for the years from then up to 1975, which was the time she felt she truly lived. She and Trinh had no money as they performed for the people in the towns and the cities and the countryside, and they knew at any moment communist bombs could drop on their heads. With every bow, she knew she might not live to sing another day. But in every moment during those years she experienced life to its ultimate, and she sang from her heart with every fiber of her being.

But why the little stage, now? In her backyard in Cerrito? The interviewer wanted to know.

“To live one more time,” she replied.

Whoa, wait a minute.

As a person who has been lucky to have lived so much, and to have known love and soul-mate-ship, I get a sense where she’s coming from. I can imagine how special and unique life was for her.

But: live one more time? Khánh Ly…did you stop? Did you let it go?

Yes, you lost your nation, your democracy, your soulmate, your best friend. Perhaps you locked it all away in a trunk for a time. Perhaps you pushed it away. It’s true that when Trinh died in the early 2000s, you did not go back. In fact, only in recent years did you go back to Vietnam.

Now in the twilight of her life, perhaps Khánh Ly has let go of some of the darkness and sadness that might have caused her to lock things away. Perhaps now she has opened the trunk, and revisited that beautiful time when she got to live.

But…we don’t need to go back if we never let it go in the first place. If we never put living, really living, away. Living in the moment, but at the same time living all those past lives that make up the moment that is right here, right now.

If we can live knowing how lucky we are, evolving and embracing and living with it all the time…if we can go all the way to the end and know we did our best to live all the time, then there is nothing to go back for. Nothing to repeat. Because we did everything with 100% intention when we had the ability to do so.

We don’t need to live one more time. We can live all of it every day. We can live all those lives always, because they are a part of us.

As we reach the shortest days of the year now, which in my case are the longest, I find myself in the twilight depths of my back garden in Santa Maria, Paraguay, in view of an flame tree in a land where blue jacarandas turn deep purple in the evening as birds go crazy.

It’s summer again, but the Andes will not see me this coming year. I will not make wine at the bodega; I won’t climb Caliboro Hill a single time.

But part of me has never left Caliboro and never will. Part of me is still there, hiking up my solitary well-worn trail in the late afternoon after work, sweat on my brow, flocks of birds rising through the brush in a cumulative rush of wings sounding like horse snorts. After the sun has dropped, part of me still hastens down the four undulations amid dry grasses, Andes alpenglow in the distance.

Each year is a new vintage. Never to be repeated.

We live it once.

And when it’s over, we get to keep living it, celebrating it!

For a choice pre-1975 recording of Khánh Ly and Trinh Công Son, click here: Cui Xuong That Gan

Haunted in Santa María

November 11, 2023

“People are wondering how long you’ll stay here,” my friend Coco told me yesterday, as he dropped off the old fridge he’s loaning me. “They claim this house is haunted.”

Coco was maybe the fourth person to tell me this.

Is that why the rent is so reasonable? I’d speculated. Is that why this house sat empty for so long?

“Tell me more!” I said to Coco, now.

“Well, the Brazilian woman who lived here before you, she had to leave. Said she’d hear someone clapping outside, and then open the door and no one would be there. Also, sometimes she felt someone lie down on the bed next to her. And she lived alone. She didn’t like it, and had to get out.”

Good for her. Good for me, I thought. I’ve been living in this adorable cottage in the center of old town Santa María for two weeks and experienced nothing but restful nights, delicious privacy, and positive energy. Everything about this place feels good, not least the grove of shady trees to relax beneath in my massive backyard. It feels like the perfect base for this next chapter of my life in Paraguay.

However, I can certainly imagine the possibilities for a haunting!

When a town is only—and only ever has been—about nine blocks long by nine blocks wide, it’s funny to call any of it “old.” Really, the whole thing is old! But my house sits at the center, at ground zero so to speak. And there is an undeniable energy.

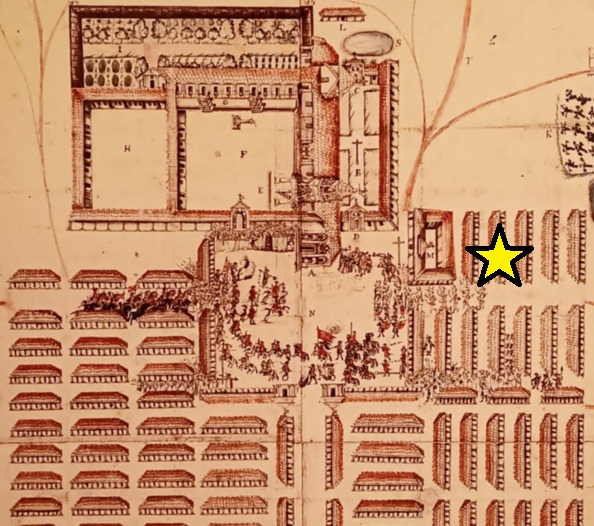

Founded four centuries ago by Spanish Jesuits, Santa María was a “Reduction”—a settlement that provided refuge to local Guaraní people from the slave bandits of the Atlantic Forest, as well as an innovative communal economy. The town had been relocated from two other sites by the time it moved to this verdant bluff in 1669, each move prompted by the need to get farther away from harassment. At its Reductions-era peak, Santa María was home to approximately 6,000 Guaraní souls and two Jesuit ones—not that different, in number, from the population today.

Half a block from my front door lies the site of the original wooden church, which fell down in the early 1900s and was replaced with an adobe church, and the gorgeous tree-filled plaza. Apparently the monkeys who live in the plaza feel the energy. And while they have their run of more than 150 towering trees, they tend to hang out in the corner of the plaza that is closest to my house.

Can monkeys clap? I wondered. Is that what the Brazilian woman heard?

Here’s what Margaret Hebblethwaite, the founder of the institute where I work, wrote about the monkeys in her book, From Santa María with Love:

“Nobody knows how the first monkey arrived, but it was found in the trees, alone and frightened, by some children in 1995. Another monkey was then brought in from a nearby hill, in the hope that they would mate. Nothing happened, and eventually it was discovered that both were female. A third monkey was then brought in, a big black fellow, and there is now a happy family swinging through the tree tops…they move around but always stay close to each other.”

Currently there are eight, and I don’t think they clap. At least they haven’t for me, yet.

Of the original Reduction buildings, almost none remain. But one does, and if I stand at my front gate and toss a stone, it will literally land in its backyard. This structure has been beautifully restored and it now houses the Santa María Museum. And man, oh man, is this ever a spooky-lovely place!

Built in 1669, the building has three-foot-thick, windowless walls. Its four stately rooms feel warm in the winter and cool in the summer. Now internally connected, the rooms were once separate family units. You can still see rings attached to the walls, where the inhabitants tied their hammocks—their preferred method of sleeping.

So, I think, if any Guaraní spirit wants to saunter down the street and lie down on the bed next to me, they probably won’t be all that comfortable, since they’re used to hammocks and not beds…

But it’s what these rooms now house that is truly haunting.

In addition to being natural musicians, the Guaraní were quite the sculptors. Under the tutelage of Antonio Sepp (of harp fame, who I wrote about last month) and his younger Italian Jesuit companion, Josef Brasaneli, the Guaraní of Santa María learned to carve wooden statues like nobody’s business. Typically, Sepp or Brasaneli would create a small statue to serve as an example, and local apprentices would replicate it into astonishingly expressive, evocative life-size forms. Of course everything was ultra-religious and mythical, which adds to the emotion, drama, and spookiness.

Eeriness aside, it’s delightful to observe the idiosyncrasies and flourishes of a Guaraní-generated carving compared to its European counterpart: straight hair, indigenous features, different treatment of clothes flapping in a breeze.

In the nativity scene in the final room, we see some rather rigid, cartoonish looking sheep standing next to baby Jesus, carved by people who had no idea what a sheep looked like other than how it had been described to them by Jesuits. And standing proudly among the sheep is a big Paraguayan bird of yore, called a kuré ka’avy, which is now extinct, and a local forest pig, called ynambu guasú, which is also extinct at least in its non-pure form.

One sculpture pair that particularly jumps out at me depicts the Archangel Michael slaying Satan.

The Euro version is standard: Michael triumphant, standing on top of the dragon-serpent, sword in the beast’s face, about to cast the foul creature to Earth where it will continue to lead the world astray.

But what’s this? In the Guaraní version, the two are still very much in battle. It looks like the devil is losing, but the fight isn’t over yet.

And…what’s this?? The Guaraní devil looks nothing like the typical biblical reptile. Rather it is Aña, the main mischievous figure of Guaraní mythology—in quasi-human form. He looks terrified.

But he also looks kind of cute.

I’m not sure what this means, but I’m sure it means something. Means a lot.

And it’s interesting. By way of this strange sculpture, installed just a stone’s throw from where I lay my head each night, I find myself captivated, drawn into the fantastic world of Paraguayan folklore, deep in the mysterious remote middle of this South American continent.

Not just that of Aña, but of so much more: of Taú and Keraná, and the curse of their seven sons, born as seven monsters after seven months of gestation—including the seventh (who is also the seventh grandson), the dreaded Luisón: the werewolf of the night.

No wonder people get haunted here!

Glizando and Trémolo

October 15, 2023

The other day, a mellow Saturday afternoon in Santa María, Paraguay, I climbed onto my bike and rode amid blossoming trees towards the institute where I teach. I knew the place would be silent and empty; an ideal time to get some lesson planning done in what I call my “Secret Garden” out back.

Then I heard it, as I rode past a house: someone playing a harp.

I looked around and sure enough, a woman was sitting on her patio in the warm afternoon beneath flowering branches, playing her harp. What else could I do except stop in my tracks, in the middle of the street, and listen?

You may think this event to be odd and rare, an unusual encounter. But here in Paraguay it is not a very strange thing.

It began more than four centuries ago with the arrival of Jesuits. One of these guys, Antonio Sepp, ended up spending the rest of his life not too far from my Secret Garden in Santa María. Born in Italy, educated in Germany, Sepp received a sizeable amount of musical and vocal training in addition to his religious instruction. After getting ordained he requested to be sent to America, and arrived in a little village called Buenos Aires in 1691. Soon after that he was dispatched upriver to one of the recently founded missions, which were called Reductions.

It may actually be true that, as Sepp and Co. plied the Paraná River playing their music, entranced locals came to the shore to listen. There is nothing (they) appreciate more than music, Sepp later wrote. When I showed them my musical instruments and the compositions of Europe, and when I played them a little (because I don’t know much), they couldn’t contain themselves.

It is certainly true that these folks had never before experienced the strings and woodwinds the Jesuits had in tow, nor choral arrangements for two, three, even four voices. Sepp and his cohort taught them to make instruments, including harps, and to play and sing in harmony. The locals proved remarkably and passionately musically adept, and, in short order made the music their own.

This was the 1690s, so the harp Sepp brought was a circa-1690s European harp. This instrument has since evolved significantly in Europe and become quite a bit more complicated. Meanwhile the Paraguayan version has gone its own way, on its own distinctive path, for 330 years to become the lovely and idiosyncratic instrument it is today.

Sepp is sometimes called the “father of the Paraguayan harp”, and it’s true he had a hand in forming the first orchestras and choruses in the Reductions. However he did quite a few other things as well, such as establish the region’s first iron foundry in our neighboring town of San Juan Bautista. If you come to visit, you will notice a pervasive orange hue in the dirt which colors your shoes, which you will take home with you. This is de to iron oxides present, particularly in local rocks called itacurú. Sepp helped develop a process to extract iron from these rocks by heating them in special ovens and reducing the oxides to native iron by mixing in some charcoal. Talk about developing the Reductions—literally and chemically!

As you may know, especially if you’ve seen Roland Joffé’s film, “The Mission”, the Jesuits were expelled in 1768. Many instruments were destroyed then, and much original written music was lost as people dispersed. The musical addiction had irreversibly taken hold by then, however. Soon folks were building new instruments from memory and local materials, and playing.

Today’s Paraguayan harp is made from tropical wood such as trebo. It has three parts which are never fully affixed to each other: a head, an arm, and a body which is a long cone-shaped sound box. Simple in appearance, the instrument is a pleasure to look at. About a century ago the head was reconfigured and more strings were added, bringing the total to an average of 36. These strings have evolved from catgut—made from sheep or goat’s intestines—to nylon, and are more loosely strung than on a European harp to give an exquisitely sonorous tone. The Paraguayan harp is diatonic, meaning its octaves are a standard five whole steps and two half steps, and it is usually tuned to F major, often by hand-carved tuning pegs. To create a flat you have to shorten the string using finger pressure or a metal tuning key, rather than push pedals as on a European harp.

The music and the playing are deeply Paraguayan, accomplished by a lot of non-Euro-style fingernailed plucking. Melody is generated by the right hand in the upper octaves, while harmony and percussive thumb-thumping rhythm happens via the left hand on the base strings. The trémolo (trembling effect) is much used, especially after a glizando (a glide from one pitch to another). The overall result is the heart-and-soul folk music of Paraguay, called “polka”, with its multiple rhythms and characteristic harmonies making it vastly different from any European-style polka. In skilled hands, a single Paraguayan harp becomes a whole polka orchestra, delivering the signature songs of Paraguay such as “Bell Bird”, “Waterfall”, “Island of Transparency”, and “Arrival”.

Rather than try and explain it to you, maybe it’s better if you listen. Here are a couple YouTube links to some pieces played by a young woman named Tessah Whale, and her friend.

If you’re like me, when you experience Paraguayan harp playing you might feel a bittersweet sense of fleetingness. Lately I’ve wondered if I’ve been witnessing something precious, something which might not be around for very much longer. Like the tropical glaciers of Peru’s White Mountains, will the traditional harp music of Paraguay retreat in the face of inexorable modern forces? After all, it’s not easy to play a harp. To keep the music going, a continuous stream of new motivated and talented players will be needed. What if young people of Paraguay stop being interested?

With concern, I asked Sabrina Ferloni what she thought.

Sabrina is one of my students here at the Institute. She’s also an accomplished harpist, having trained with our harp school for the past four years. On an interesting side note, her family is originally from Italy—the cradle of the harp.

“Yes, my father’s last name is Italian,” she told me as we began talking. “His great-grandfather came from there, from what he has told me. But Italian culture doesn’t really influence us that much.”

“What influences you?” I asked. “And how did you arrive at the harp?”

“I came to the harp mainly because of my father, and I am very grateful to him,” she replied. “From a young age he listened to a lot of cultural music, you could say, and this affected me and my brothers a lot. We used to listen to my father’s music during trips in the car: Paraguayan polka, everything like that. And in it was the harp, which attracted me because it was so memorable. Because of my father we all learned about and experienced many musical types and styles, and we liked them. Now, neither my brothers nor I care much for the fashionable varieties of music of today, such as reggaetón and so on.”

“How does playing the harp make you feel?”

“When I play, I usually feel tranquility. It makes me relax, mainly because playing music is a good method to listen to music. It can be relaxing for the mind. Also, knowing that I am playing in a group and that I am constantly learning something new makes me feel really fantastic.”

It was great to hear this enthusiasm from her as I geared up to voice my concern.

“How do your friends and cohort view the harp?” I asked, tentatively. “And the violin, and traditional music in general?”

“At school I hear a lot of Paraguayan music being played by my fellow students. Of course they listen to other styles as well, but many are very attracted to the instruments—especially the violin and the harp—and they are interested in learning. They like the sound, but they also know they are hearing something that is part of the future of Paraguay. They like the passionate nature of the music. However, many do not have the opportunity to learn.”

“So you see the popularity of this music continuing among young people?”

“Although it sometimes may not seem like it, the popularity endures. Often I have thought that young people might give up this style because they would think it was out of fashion. But it is part of the culture of Paraguay, and I don’t think it will go out of style, nor will young people stop listening.”

Yay! I said to myself. I feel better now.

Outwardly, I said, “Can I write about you in my blog?”

“Yes, of course.”

“And is it possible for me to take some photos of you with your harp? And hear you play some more?”

“Yes, of course. Right now, I don’t have access. But you can come to our practice on Sunday if you are available. We will be in a whole group.”

Tereré Hour

September 13, 2023

Tereré hour at the Olmedo Zarza house happens at about eleven o’clock in the morning. This is around the time I get home from teaching morning classes here in Santa Maria de Fé, Paraguay. Don Sindulfo is usually home at this time, on his lunch break from the local sugar factory, and is sitting outside next to his wife, Elva. They sit in their lawn chairs and pass their stainless steel guampa (cup) with its steel straw back and forth between the two of them, sipping, with Elva regularly topping-off the steeped herbal concoction with iced water from a pitcher. As they sip they talk, and talk, and talk. Never before have I seen a couple married for so long sit together daily and talk to each other so much.

Tereré hour is not to be confused with yerba mate hour, Rufino, their son, who is another of my housemates as well as one of my students, informs me. Yerba mate hour happens at around nine, after I’ve already left for school. Rufino takes part in this one, and the beverage is almost the same as tereré except the water is hot. This feature has been pretty important during the chilly mornings of the past month, when winter has teased us into believing it might be leaving but not yet given up its grip.

Now it was Sunday morning, and tereré hour was being augmented by several factors: (a) the sun was out and it was getting warm, (b) relatives were visiting from out of town, to enjoy Santa Maria’s annual festival, and (c) the barbeque was fired up and smoking with roasting meat: an asado.

It was our third asado of the week. We’d celebrated Rufino’s 43rd birthday on Tuesday with not one but two asados—one in the day and one at night—each followed by birthday cake and singing and requisite icing smeared on Rufino’s and his mom Elva’s noses.

These festivities had augmented a week-plus of other celebrations around town, with much, much more asado-ing, and church masses and religious gatherings, and all-night live music dance parties at the local event center called the Polideportivo. And the night before, Saturday night, I’d attended a bullfight.

“Pete! Time to eat!” Rufino called to me now.

Intoxicating aromas of hot smoking beef ribs wafted in through my bedroom door and I needed no further encouragement. I’m not yet close to tired of asados and don’t think I ever will be. As an added bonus, the filling of the tummy with a big pile of roasted meat at noontime facilitates a nice snooze afterwards, during a subsequent siesta.

Which I had.

I remember a similar siesta a few weeks ago, back in mid-August. I awoke on a Saturday afternoon to the sound of children’s music, and stepped outside my door to see what looked like a child’s birthday party taking place in our driveway. Kids were running around, playing games, laughing, enjoying fizzy drinks, and eating snacks. Elva informed me later that this was something she organized every year for the poorer children of the neighborhood, to give them a bit of fun in celebration of National Children’s Day. She had more activities planned for the kids that evening at church.

“Aha. Children’s Day,” I said.

In Paraguay this occurs on August 16th, and this year it had fallen on a Wednesday. On that day I taught my adult classes in the morning and the evening, but not my children’s class in the afternoon. In observance of it, we’d given the kids the day off.

“Children’s Day,” I repeated, and couldn’t help but shudder, thinking of what I’d learned about its origins.

National Children’s Day commemorates an event that occurred on August 16, 1869. On this day, Paraguay was in its final year of its catastrophic six-plus year War of the Triple Alliance, which it fought against Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay over long-simmering territorial disputes and attempts at political domination, among other reasons. During this war Paraguay lost some territory, and also lost nearly 70% of its population—including more than 90% of its adult male population.

By August of 1869, the capital Asunción had fallen and what was left of the Paraguayan army was in full retreat. Still, dictator Francisco Solano López refused to surrender. By now the overall population had been decimated and the army had been reduced in size to about 600 poorly-armed men.

To augment his forces, López rounded up about 3,500 boys, mostly aged 10 to 14, and dressed them up as much as possible to look like men. He added a few women, old men, and wounded veterans, and retreated to the hills east of Asunción.

The Allies, led by Brazil, caught up with them at a place called Acosta Ñú, which means “big field”. Here, López’s ragtag juvenile army were forced to confront a 20,000-strong, merciless Brazilian juggernaut. Witnesses reported the children clinging to the legs of the Brazilian soldiers and pleading for their lives, only to be impaled and decapitated. Once their front collapsed, the children unsuccessfully tried to flee with their relatives. The Brazilians, unrelenting, proceeded to set fire to the battlefield and the nearby field hospital. It’s estimated that 2,000 Paraguayans, mostly children, were killed in action that day, and another 1,200 to 1,500 were captured and subsequently executed.

Today, National Children’s Day is a day of merriment, with celebrations and fun activities for children happening throughout the country. Interestingly, the historical origins of the day are not hidden or obscured. Rather, everyone knows it’s a day for paying homage to the “child martyrs of Acosta Ñú”; a day to commemorate their heroism and bravery. In Paraguay the “hero child” who died defending his country is part of the national identity.

So yeah, it’s interesting. Instead of marking this day with solemnity or avoiding talking about it altogether, it is instead celebrated on its exact anniversary as a wonderful day for children.

What about this guy Francisco Solano López, the dictator responsible for it all? The man who made possible not just the slaughter of all these children, but who prosecuted the whole insane hopeless apocalyptic war way past its expiration date and refused to surrender, even after the men and then boys and general population had been annihilated?

Postwar, Solano López’s reputation understandably sank into ignominy. Then it proceeded to go up and down over the decades as political climates and revisionist histories shifted, settling decidedly into the category of “national hero”—every country needs them!—in the second half of the 1900s during the Stroessner dictatorship. Nowadays, avenues and bridges and schools and all that kind of stuff are named after Solano López. In fact, the president’s office is located in López Palace.

Aside from López the legend, what happened to López the person?

After the Battle of the Children, he was able to keep his “war” going for another seven months. Brazilian troops finally caught up with him and shot him dead at a place called Cerro Corá on March 1, 1870. López resisted until the very end, and his final words reportedly were, “I die with my homeland!”

This quote is a big part of the modern day hero-worship machine. Which is strange, because his homeland really did die, pretty much, as did he; one of the very few adult Paraguayan men able to stay alive all the way until 1870.

I know what you’re going to say next.

“Please don’t tell me he’s on all the money.”

I’m here to report that, oddly enough, he isn’t. The largest note in Paraguay is 100,000 guaranís, about $14, and that honor goes to pioneering Jesuit missionary Saint Roque González de Santa Cruz. Next up is the 50,000 note, graced with the mug of legendary guitarist and composer Agustin Pío Barrios. The 20,000 note has the non-identified face of an archetypical “Paraguayan Woman”, and the 10,000 note gets founding dictator (i.e. two dictators before López) José Gaspar Rodriguez de Francia. On the 5,000 note is Dictator Number Two: Lopez’s dad, Carlos Antonio.

It’s not until we get to the lowly 1,000 guarani coin, worth about fourteen cents, that we finally see the face of Marshall Francisco Solano López.

Which isn’t to say there aren’t still plenty of things you can buy in Paraguay for 1,000 guaranís, Paraguay being Paraguay.

But also, because Paraguay is Paraguay, tereré isn’t one of them. Actually, that’s not quite correct. You certainly could buy some tereré from a sidewalk tereré seller for 1,000 guranís if you wanted to.

But all you really need to do if you want some tereré is go sit with someone at tereré hour. And they will readily, naturally, happily, pass you their guampa and straw.

An Island Surrounded by Land

August 12, 2023

If not for the clocks on the wall you could imagine yourself in a bus terminal in a small city, somewhere in the USA, some time ago. Maybe the 1990s? Metal chairs, epoxy floors, fluorescent lighting. A woman stands behind an all-night snack counter where the coffee is self-service, in a Styrofoam cup from a timeworn pot, 70 cents.

“Free refills,” she says with a smile.

I pay her in guaraníes because this is the arrivals hall at Silvio Pettirossi International Airport in Asunción, Paraguay. The clocks indicate it’s 4:18 in the morning here, and an hour later in both São Paulo and Buenos Aires. I decide to sit and wait for daylight before continuing my journey.

Later I’m in dawn light out on the main road, boarding a city bus to the center to eventually see about getting a SIM card in my phone. It’s a bustling morning and everyone is paying by holding a card up to a magnetic reader. I wave a 10,000 guaraní note at the driver and ask if I can pay in cash.

“No,” he says, and with zero hesitation, says to the young man who boarded ahead of me, “Hey, can you pay for this guy?”

The man, with equally zero hesitation, nods and holds up his card to the reader a second time.

Beep!

And in this manner I am initiated to Paraguay, and receive my first exposure to paraguayidad.

“What kind of a place is this?” I ask myself repeatedly during the day, as I roll four hours southward through gorgeous green countryside emerging from winter, along the narrow meandering two-lane national highway. It’s an unknown place, that’s for sure—to the outside world that is. As a corollary, I sense it is not so much a misunderstood place as a non-understood one.

In the weeks before my departure from the USA, conversations about it with people went something like this:

Physician Assistant at my doctor’s office: “Any great plans for the summer?”

Me: “Yes! I’m moving to Paraguay to work for the rest of the year.”

Physician Assistant: “Oh, how fun! Where is it?”

It’s true: Hardly anyone seems to know what Paraguay is, let alone where it is.

One of the reasons for this is that there aren’t very many Paraguayans to tell about it. The total population is less than 7 million, and well over half live in the greater Asunción area. This is a country two-thirds the size of Texas.

The reasons for the low population are complex, and disserviced by attempting to describe in a nutshell, and related to tumultuous history and uncommon geography. One episode still exerting its effects occurred over a century and a half ago: the 1864-1870 Triple Alliance War between Paraguay and Brazil-Argentina-Uruguay. This is a war few in the world know about (I didn’t until now), and in it, Paraguay lost over 90% of its male population and over 60% of its overall population.

Unsurprisingly, Paraguay today is an immigrant melting pot to the extent that I pass for Paraguayan until I open my mouth. And when I do open my mouth, I reveal myself not so much by my accented Spanish but because no Guaraní words come spilling out.

Guaraní?

It’s true: In a country of immigrants, in addition to Spanish, nearly everyone speaks, but more importantly thinks and feels in the indigenous language Guaraní. This is despite the fact that very, very few indigenous people—Guaraní or otherwise—still exist here.

Thiago, a student of mine, positively glowed the other morning when we were discussing the bilingual nature of most Paraguayans.

“I love speaking Guaraní!” he exclaimed, his eyes sparkling, shifting in his chair. “When I speak it, I feel I am more myself.”

Unique. Original. Idiosyncratic. These are some of the adjectives that come to mind when I ask myself, once again, “What kind of a place is this?”

How lucky for me, to have the opportunity to live here and learn. On a planet where I constantly feel uncomfortably squeezed and pressurized by relentless forces which seek to standardize everyone into a uniform way of living—when all I really want to do is be the protagonist of my own story—I am grateful to get this chance to live and work in such a nonstandard place.

I’m living in a beautiful, peaceful town called Santa Maria de Fé. Situated on a verdant bluff with a Lourdes-like spring running below, the town is only about nine blocks long by nine blocks wide. Though pint-sized, it is home to a community-based technical institute and a longtime and well-regarded English academy that is run by the Santa Maria Education Fund, where I teach English and may soon branch into chemistry and maths.

It’s an enchanting place, and no stranger to turbulent history. Santa Maria was originally one of the 30 Jesuit missions, known as Reductions, which were founded in the early 1600s. It was run as such until 1768, when the Jesuits were violently expelled from the region. If this story sounds familiar to you, perhaps you’ve seen Roland Joffe’s moving 1986 film, “The Mission”.

Here, situated around a tree-filled plaza that is home to an amicable group of monkeys, Santa Maria still has a few buildings that date back to its Jesuit origins.

There’s a whole lot more going on here of course, and it will take some time to begin revealing itself.

For now, something I can’t help but take in straight away are all the blooming trees! As spring begins to unfold, so do the abundant arboreal flowers of Paraguay. Beginning to burst forth now are the joyful the yellow trumpets, the flamboyant pink lapachos, and—my favorite—the soulful blue-purple jacarandas.

Updates from Home

July 13, 2023

First, an update on Thai politics:

Parliament convened on July 3, and “raising of hands” to select the new prime minister finally took place today, July 13th. The outcome? Surprise surprise, Pita Limjaroenrat, the leader of the party that obtained the overwhelming majority of popular votes on May 14, was blocked from becoming prime minister. He needed 64 of 250 unelected senators to vote for him, and only 13 did. These senators were appointed by, and are beholden to, the monarchy-military establishment, and they don’t care who won the most votes.

“It’s not our job to listen to the people,” Senator Prapanth Koonmee stated on June 28, as a preamble.

This, in a country whose name literally means “free land,” of a people whose name literally means “free people.”

My source on the ground told me they knew this would be the outcome a week ago, and the key issue is that the King feels extremely threatened by a prospective government that would revise Article 112 to allow the people to talk about him and question his power and relevance without getting thrown in prison.

Things are apparently quiet in the small towns right now, hours after the vote, but large-scale protests are guaranteed in Bangkok and Chiang Mai. Whether or not the senators think it’s their job to listen, the people are going to speak.

I left Thailand before this happened and came home to Colorado, where I’m hanging briefly before heading off to new lands. Summer solstice seems to be my time to be in Colorado. This June, uncharacteristically, I didn’t put ice cubes in my coffee nor did I sleep in the basement, the reason being that Denver and Seattle swapped their weathers this year. It’s been mostly cool and wet here, the wettest June on record in fact. If we don’t get a single drop more of rain, or another flake of snow for the rest of 2023, we’ll still end up with an average amount of annual precipitation.

How did the Cabin Creek snow gulley fare? The one up on Mount Meeker? You can go to my July post from a year ago to understand or remember what the heck I’m talking about.

As of today, it’s still a little bit there. This makes two years in a row of it lasting until July—and a landmark year of it lasting until mid-July!

It’s been pleasant, walking a mile out into the wheat fields each day to look up at the mountains and monitor the gulley’s melt progress. Also, I get to greet and hang out beneath my old friend, a towering Fremont’s cottonwood tree.

This year I’ve done this to the accompanying cries of a soaring pair of Swainson’s hawks, who have moved in for the season and who don’t seem to share my enthusiasm for the Cabin Creek snow gulley. They’re too busy hunting for prey while being harassed mid-air by gangs of little birds.

Meanwhile, back at the bodega in Chile, times have been challenging.

Deadly floods in Chile after rains swell rivers, Aljazeera announced on June 26.

The winemaking regions of Maule and Biobio have been severely affected, with vineyards reportedly underwater, informed another news outlet.

How are you guys doing? I texted Javier, my bodega boss, with my free hand while I continued googling. How are you managing with the floods?

I continued reading while I awaited Javier’s response. It turns out the solstice—which is the winter solstice there—marked the first day of a front that brought the heaviest rainfall the Maule Valley has seen in thirty years. In only six days the bodega received more than a fifth of its annual rainfall. More significantly, the front had an unusually high freezing level of over 9,000 feet, which meant that rain fell on top of winter snowpack in the Andes, melted it, and caused the river to burst its banks.

My phone vibrated.

Hi Pete! Everyone’s fine. And you?

I noticed Javier had said everyone is fine, not everything is fine. That’s a subtle difference in Spanish.

Then he sent me drone footage of the river. And every thing did not look fine!

There are silver linings, however. Number one: everyone is fine. Number two, the bodega’s 200-year-old País vines are located significantly above the river level and are probably safe. Number three, water is being replenished in this parched land, and next year’s dry-farmed grapes are likely to be plentiful.

Now I’m sitting here in Colorado, thinking about Chile, and about Thailand, and other places I feel connected to…for example, texting a friend in Ghana who has serious health problems, and writing to my elementary school friend who is in prison in Washington State. Next week I head off to a new job in a new country. It will be a whole new experience, a new life to forge. It’s a little disorienting sometimes, to focus on where I’m going while giving attention to where I’ve been.

But for now, I can just be here in Colorado.

And also be Willie Wonka!

The owners of the Jesters Dinner Theater did me a huge favor and gave me this fun, silly, psychotic, sadistic role to perform whilst I’m home. I have three more shows to do, this weekend: Friday night, Saturday afternoon, and Saturday night. Great seats are still available!

Butterfly Pea Flower Tea

June 14, 2023

A good thing to do on a warm afternoon in Thailand is have a nice refreshing glass of iced blue tea.

It’s made from the deep cyan flowers of the butterfly pea plant, which grows like crazy around here, unbothered by pests or infirmities. The tea, steeped from the flowers along with some dried lemongrass, arrives at your table along with a small pot of honey and a wedge of lime.

Gazing into the calm azure color is a relaxing experience, one that can evoke vast oceans or endless skies; in other words, freedom. It might seem like a good metaphor for this country, which throughout history remained an independent Buddhist kingdom and was never subjugated by a colonial power. Indeed, the word thai literally means “free.”

But is Thailand a free place?

Back at the tea table, consider the wedge of lime. You don’t need to use it. You can enjoy your tea with just the honey, and drink down its anthocyanin-infused blueness in its entirety.

But if you squeeze the lime into it and stir, something happens. The tea turns into something that it didn’t appear to be before: bright pink and purple. This acid test, this litmus test, has revealed a character different from the previous one.

As the old adage goes, things are not what they seem.

Here are two lime drops to squeeze into the blue pool of purported Thai freedom:

1. Religion is compulsory.

There is no escaping Buddhism in Thailand. Magical supernatural thinking is organized and indoctrinated, top-to-bottom. You are required to pray, daily, repeatedly, from a very young age. If you go to school you have to pray to Buddha, and to the king, as a central part of your daily classwork. I’m talking about public school. Every day, you must repeatedly prostrate yourself and press your face into the floor. And every Friday afternoon you have to chant for an hour in a language no one understands.

In a kingdom only twice the size of Wyoming, there are over 44,000 temples and counting. The ones already built only get bigger. Incalculable resources go from the public’s pockets into them. These are gold-plated temples, funded by the millions’ superstitious fears of not having enough “merit” to outweigh their demerit.

Hence, monkhood is a popular and lucrative career in Thailand (for men; women are “dirty” and prohibited).

Guess what the number one priority of all government leaders is. Serving the public? Doing their jobs? Nope. Their overriding, fundamental responsibility is to “uphold religious traditions”.

2. It’s a kingdom.

There is no such thing as public land. All land not privately-owned, including for example the national parks, is “of the king.” Same goes with anything else normally set up for the public: healthcare, education, transportation, all government agencies and employees, law enforcement, and especially the military. All are “of the king”. And this king has real power, near-limitless wealth, and is cloaked in deification by Buddhism. As you have probably heard, criticism of him is prohibited. In fact everyone needs to pretty much forgo any open mention of the monarchy, almost all of the time but especially in the context of discussing any of the nation’s problems. Talk about ignoring the elephant in the room.

Of course, no one votes for the king and no one has any say in who the next one will be. This is of particular concern now in 2023, since the current monarch is over 70 years old, looks like death warmed over, and the options for succession have been winnowed down to a fashionista daughter, an autistic son, and a fourth and childless wife who is a former flight attendant.

This past year, the kingdom’s budget for education was abruptly and unceremoniously cut in half. Same went for public health. Where did the money go? To the military—in a country with no serious external enemies. The job of the military is to protect the monarch from his subjects and ensure he remains in power.

Hence: being a soldier is a popular and lucrative career path in Thailand.

A real litmus test for Thailand’s freedom, or potential thereof, will arrive next Tuesday: on June 20, 2023. You probably heard about the election that took place here a month ago, in which the Move Forward party won a resounding victory. Central to this party’s platform are items such as reforming the education system into something that teaches the population how to read and write and do arithmetic (instead of how to draw and color, dance, and pray), and changing the law so that the population can begin to have a conversation about the monarchy.

Before a new government can be formed, however, an event called “raising of hands” must take place. This is when the senators, who were not elected, and who are largely and staunchly pro-status-quo with respect to the monarchy and military, join the elected lower house in casting their votes for a new prime minister. Unless 63 or so of these 250 senators agree to support a coalition led by Move Forward—and many have stated flatly that they won’t—the people’s choice will not move forward.

What happens after that remains to be seen. It’s going to be interesting.

The House of the Bad Gringo

May 12, 2023

“You still need to visit the House of the Bad Gringo,” my workmate Rodolfo told me a few weeks ago. “I’ll take you there one of these days after work.”

However our hours at the winery here in Caliboro, Chile remained heavy and long, as vintage 2023 entered its final stretch. Meanwhile autumn deepened, days shortened, and dusk crept into our 6 pm quitting time. Finding the time to visit la casa del gringo malo proved elusive.

“I’ll give you some background,” Rodolfo told me, as we worked side by side. “Here in Chile, up into the 1960s, workers in the countryside had basically no rights. My father was one of them.”

“As was mine,” said Cecey, our lab technician, who had arrived to take a sample. “Papí left before sunrise, worked all day in the campo, and came home after sundown exhausted. Then he got up and did it again.”

“For no money,” added Rolo. “Only for food.”

“And chemical exposure,” said Cecey. “So many died of cancer.”

Including Cecey’s father.

It’s true: the 1960s Chilean campo was a truly harsh place for workers, a throwback to medieval times. Being in Spanish, the names were different, but the roles were the same. In place of the lord was the patrón, or hacienda owner. In place of the serfs were the inquilinos. This system of servitude, exported by Spain to its New World colonies, was still going strong in Chile as late as 1962.

An inquilino in Chile was a laborer indebted to a patrón, who allowed him to make a small farm on a part of his property in exchange for labor, without pay. Compensation was in the form of the privilege to grow food in nonexistent spare time.

A third party often figured into the equation, and this is where the Bad Gringo comes in. Onsite management was often performed by a paid administrator who was usually brought in for a fixed term, and sometimes paid a share of the hacienda profits in addition to his salary.

Somebody’s got to crack the whip!

“So the Bad Gringo was basically the slave driver,” I said to Rolo.

He nodded.

Finally, on Tuesday of my final week, we got off work a little early. “You ready to visit the house of the Bad Gringo?” Rolo asked.

“I’m ready,” I replied.

Bright autumn sun slanted across the landscape as we climbed into his white pickup and bumped along the dirt road to the township and river crossing a couple kilometers away. When we reached a large, old crumbling house not far from the riverbank, the sun was backlighting aspens to illuminate their shades of rust and gold. Recent snowfall glowed on the Andes above to the east.

“This place was really something,” Rolo told me as we walked the faded verandah of the adobe structure, beneath its huge sloping terracotta-tiled roof.

“What was his name?” I asked.

“Renée de la Fuentes,” Rolo said, grinning and almost spitting out his words.

“Aha! Then he wasn’t from the United States,” I said, feeling a bit relieved.

“No, I think he was a Spaniard. But here in Chile, all such foreigners were called gringos.”

We walked around to the back of the house, where amidst the overgrowth I could envision the lawn, the chairs, the tea being served. “These trees were not here back then,” said Rolo, motioning with his arms. “They would have obstructed his river view.”

“What became of him?” I asked.

“No one knows. He left during the reforms.”

Rolo was speaking of the agrarian reforms which took place in Chile between 1962 and 1973. During this period, about 60% of Chile’s agricultural land, formerly held by the elites, the Catholic Church, and the State, was redistributed to the people whose families had worked it for generations.

“I’m not surprised the Bad Gringo high-tailed it,” I said.

And I thought: But he had stuck around, he might have gotten his job back!

In 1973 the Pinochet dictatorship landed, and along with it, counter-reforms which saw a third of the expropriated land returned to its former owners. As the export-driven, right-wing libertarian economic system cranked along over the next decades, many former peasants who’d managed to hang on to their land grants were forced to sell, since they had no access to credit or capital to invest in improvements. Today, land ownership in Chile is more concentrated than ever, and largely in the hands of corporations.

But Renée is long gone, and as his nickname more than implies: “Good riddance.”

As I stood with my friend in the fading autumn light, I felt a little sad for the Bad Gringo. It truly was his loss.

I say this having worked two seasons here and more than fallen in love with this place. Caliboro has become a part of me and will live on with me forever. I feel an immense joy to know that it is here, and that I can come back whenever I want to, or need to.

I feel so damn lucky.

“Come,” said Rolo. “Let’s go to my house now. You can meet my daughters. I’ll show you my trees.”

“Yes!” I said, “To the house of Rolo!”

Off we went, towards a modest cream-colored bungalow set a stone’s toss from the river amidst gardens, ducks, beneath the snowy Andes, woodsmoke emanating from its tin chimney.

A palace for sure.

Other Things Chileans Do With Grapes

April 11, 2023

The Southern Harvest Moon was full this past week, and devoutly-observed Chilean Easter gave a brief respite from the intense agricultural work of autumn. What a great time to kick back and enjoy some arrope and chicha!

Even if you already know what these things are, you might not be familiar with the distinctive traits they have in Chile, and the role they’ve played in the history and heritage. You might also not know about what they’ve been up against, to survive into modern times.

First we’ll examine arrope, or grape honey. This has been a homemade treat since at least ancient Greece, and might be the more familiar of the two (the IHOP version does not count). In Chile’s central valley, and particularly here in the Maule, arrope must be made from País, the People’s Grape, which is discussed in the previous post. After País is harvested, not all is turned into wine. Some of the fresh juice gets drawn off into plastic jugs and sent to local kitchens.

Traditionally it went into huge copper pots positioned over fire, where it was boiled and stirred for a day. When making arrope, it’s important to maintain a rolling boil in order to prevent the ultra-sweet juice from fermenting, and to stir continuously while simultaneously adding more liquid. Needless to say, it’s an art. At the end of the day, 200 liters of juice becomes 60 to 80 liters of syrup, which gets decanted the following day, boiled again, and then bottled for a one-year-plus shelf life.

In Chile, arrope has always been made exclusively by women, using skills passed on from mother to daughter. Real men don’t make arrope.

But just imagine. Take a time consuming, rural, gender-specific, inherited task performed over a hot fire, combine it with a disappearing ingredient (País), and top it off with young people moving to the city. What do you think are the chances of arrope production thriving in the twenty-first century? Especially when you can go to Lider (a.k.a. Walmart) and buy a half gallon of fake maple syrup to drizzle over your sopapilla instead?

More on that in a moment.

Now let’s examine chicha. “Ah, chicha!” you might say. “Raw corn beer of the Andes!”

Yes in general, but in Chile: No.

Yes, in that alcoholic beverages made from fermenting vegetables and fruits, collectively known as chicha, were deeply rooted in indigenous South American cultures long before the arrival of the Spanish. But no in that, in Chile, the term refers specifically to the semi-fermentation of grapes, and more specifically, País grapes.

Two types of chicha emerged in Chile after the Euros arrived: raw and cooked.

Raw chicha is simple to make and consumed only at harvest time. All you do is let some fresh grape juice sit in the sun for two or three days until it is mildly alcoholic but still very sweet. Then drink it.

Cooked chicha is more complicated. You do the same: let the juice partially ferment. If you live farther south you might add some apple juice and spice it with basil, but here in the Maule it’s País and only País. Then you halt the fermentation by boiling in a copper pot and adding some sulfur, along with some vine ash to neutralize the acids, and transfer the liquid to barrels or clay jars, which you bury in the ground or store in a cool place through winter.

By springtime, in September, the sweet, fizzy, lightly alcoholic drink is ready to be bottled and corked for immediate sale.

Cooked chicha lasts four to six months before going bad, which means it is ready in time for spring festivals and needing to be drunk. It’s a refreshing beverage with a little bit of a kick. The alcohol content is lower than that of wine, which makes it quaffable in large quantities and perfect for parties and celebrations. Traditionally, chicha has been important for the Independence Day barbecues which occur on the 18th of September. As such, it has historically been a very, very popular drink in Chile.

Chicha hit its peak production in the mid-to-late 1800s, when railroads facilitated distribution of the semi-perishable product and print media fostered massive competing advertising campaigns. In 1883, about the same amount of chicha was produced in Chile as wine itself.

Then it met its downfall.

It was snobbery that caused it. As the twentieth century dawned, everything French became embraced by the Chilean elite. Especially where grapes were concerned, only French ways and French grapes would do for them. The privileged few scorned the local País grape, and despised traditional Chilean viticulture in general with its myriad methods and styles. They used their power and influence to coerce the general population into thinking same way, and to conform to their view that chicha and its ilk were poor quality drinks made from poor quality vines using deficient production methods; i.e., unhealthy beverages that should be banned.

Large wine factories in the hands of a few wealthy families gained ground and old ways lost out. By 1923, only about a twelfth as much chicha was made as was wine.

Relegated to bumpkin status, chicha struggled along, kept alive in deep Chile, in small País grape-growing places like here in the Maule—areas with a strong huaso culture. Here, folks kept on making raw chicha to drink at harvest time and cooked chicha to enjoy come September.

A word about the term “huaso”:

Huaso is to Chile as cowboy is to USA, as charro is to Mexico, as gaucho is to Argentina-Uruguay-Paraguay. In Chile, a huaso is a skilled horseman and cattle and sheep herder, who is also involved in farming. His sweetheart may be called a huasa, but is more often than not referred to as a china. Huasos ride horses of course, and wear brimmed straw hats called chupallas, as well as ponchos and other typical garments. The term possibly comes from the Quechua word wakcha, meaning “orphan” and also “free and homeless,” or from wasu, meaning “rough and rustic.” You get the idea. Huasos are still around in Chile; I’ve worked the fields here with a guy named Miguel who drives no car and travels only by horse, arriving each morning along with a pack of white dogs. The lead white dog never lets me go near the horse.

Naturally, chicha has traditionally been an important drink for huasos. A real huaso drinks his chicha from a cacho, which is a specially-fashioned bull’s horn fitted with nonrusting metal at the drinking rim.

As Chile modernized through the 1900s, huasos were often disparaged. However it was huasos who saved chicha from oblivion.

Picture the day of September 18th, 1931, and the Independence Day military parade that took place in Santiago. It was the first such celebration since the beginning of the Great World Depression. The country was reeling in the most acute economic crisis in its history, and the great world powers weren’t helping. It was a painful time, but also a time for reflection and reassessment of what it meant to be Chilean. What was so great about the French anyway? many people were wondering. A collective psyche was emerging that the country would have to manage on its own, in its own way.

Non-coincidentally, in 1931, for the very first time, huasos were included in the parade.

Thereafter, they became a fixture in it.

Fast forward to 1948, when things kicked up a notch. That year at the parade, one of the huaso participants rode over to where the President was sitting and, in front of the nation, offered him chicha from his cacho.

What was President Gabriel González Videla to do at that moment? It was a serious breach of protocol, something to definitely be frowned upon in a nation as formal as Chile.

Here’s what he did: He drank the chicha, and thanked the horseman.

The effect was exactly the opposite of what might have been expected. The public fervently approved.

The next year, the same gesture was performed, except this time the chicha was presented to the President in a cacho decorated with the colors of the Chilean flag. And he drank from it and proclaimed, “Everything is for the homeland, that’s how things have to be!”

And in this way the tradition of drinking chicha in September became re-cemented as a central part of the nation’s culture.

Nowadays on September 18th chicha is in prominence at the rodeos, the dances, the barbecues, and especially the fondas (food fairs), where even in the heart of Santiago it is all the rage to go for a big refreshing pitcher of iced chicha.

Here at the bodega where I work we do not make chicha, but there are several artisanal chicharías in the region that do. My foreman, Kako, told me last week that the next time País grapes arrived at the bodega he was going to get a jug of the fresh juice and make some raw harvest chicha.

Sure enough, the País came in today and Kako got his jug.

Last week, at one of the big stainless-steel fermenters where we had just gotten a different batch of freshly-crushed País grapes going, I spied my workmate Emelia drawing off juice into about two dozen five-liter plastic jugs.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“These are for a woman in the village,” Emelia explained. “She’s going to make arrope.”

So there you have it! Here in Caliboro at least, along with chicha, arrope is not dead! At the regional fondas in September, along with their iced chicha, people will be able to enjoy a hot fried sopapilla smothered in homemade arrope.

The People’s Grape

March 13, 2023

“Sweet. And dense,” I said to my workmate Rodolfo early one morning last week, as we sampled the grapes that had arrived in one-ton cubical bins for processing.

“It’s País,” he replied, nodding and chewing solemnly.

We were getting ready to fire up the de-stemmer and move about 6,000 kilos into a fermentation tank here at an old winery in Chile’s Maule Valley, where I am thrilled to be back and working my second vintage.

“País,” I echoed, gazing respectfully at the grapes in my hand.

In Spanish, país means “country”. But in Chile it means a lot more.

Rodolfo held up some grapes and studied them. Then he told me (in direct translation), “The small País growers, the ones who still have it in the ground, they go on clinging to their vines.”

“That’s good to hear,” I replied.

Because this grape has a story.

The story began in the 1500s, when Jesuits arrived and needed wine to perform Eucharist. They couldn’t find any grape-like berry growing in Chile, so they were forced to drink oxidized fermented grape juice shipped from Spain. This beverage was so totally nasty that it hardly sufficed as a proxy for drinking Jesus’s blood and for something to remember him by. In short order, some raisins arrived on a galleon from the Canary Islands were planted. The year was 1548.

Thanks to DNA, we now know that what was planted was not a native Canary grape. Rather it originated in La Mancha, Spain, where it was called Listán Prieto, and where it has long been extinct. It was also known as “common black grape.”

In addition to Chile, this common black grape also made its way, courtesy of the Jesuits, to the Dominican Republic, and onward to Mexico and Peru, and farther onward to California (where it came to be known as Mission), and Argentina (where it was called Criolla Chica). It is now extinct, or nearly so, in all of those places.

In Chile, País absolutely took off. Young vines grew into large bushes all by themselves in rough soil without irrigation, and produced enormous crops of big, irregular berries that made a weak watery wine. This wine worked fine for sacrament, and wasn’t a problem for recreational drinkers either, especially since they could boil it into a concentrate or distill to make pisco.

For the next 350 years or so, País reigned supreme as Chile’s main grape. The vines grew, and grew older.

País’s dominance wasn’t seriously challenged until the late 1800s, when some Chileans got rich from mining and made trips to France, where they fell in love with Bordeaux varietals. They brought back Cabernets, Carménères, and the like, and planted them mostly near Santiago.

At first these vines were grown mostly to make wine for a few rich people. In poor regions such as here in the Maule, farmers had not the money nor the desire to replant more lucrative vines. Why should they, when they could make some quick cash by selling the País from their inherited family fields to local bodegas such as the one I’m currently working in? Here the grapes were turned into a cheap, light, fizzy, bulk wine for immediate consumption. País farmers also had the option to make wine themselves, and sell it to neighbors in jugs.

As such, through this period País never stopped being the grape of the Chilean campesino, “The People’s Grape. It remained the best bet for anyone looking to make a large quantity of grape alcohol at a low cost.

And the vines continued to replicate, and grow even older. And their roots grew deeper.

Fast forward to the 2010s. The situation is looking dire for País. Chile has experienced a wine revolution and is now respected around the world for its Cabernets, for its Carignanes. The lowly old País, whose untrained vines up until the late 1990s occupied more than 200,000 hectares, has been getting ripped out like nobody’s business and replaced with Bordeaux varietals as well as other exportable crops like cherries and plums. The amount of land taken up by the People’s Grape has dwindled to—gulp—less than 10,000 hectares.

Less than 10,000 hectares of País, growing mostly in poor surface soils that don’t support much other agriculture, growing as untrellised bushes as they have for centuries. Gnarled, thick, weathered brown stumps, rustic roots reaching deep into volcanic soil, healthy, not requiring irrigation, suddenly sprouting small bunches of dark purple grapes in summer.

Lower yields result in ripe País grapes being concentrated. And old roots going deep into volcanic soil give added complexity and expression, or “terroir”. Truth be told, during this past half millennium, this common black grape has evolved significantly, and has metamorphosed into something unique and special—something distinctly Chilean.

“Stop!” Rodolfo called to me for the fourth time that morning, as I pitchforked grapes into the de-stemmer. The gnarly País stems had once again clogged the machine’s outlet. The separated, crushed fruit had been doing a similar number on the hopper feeding the screw drive and peristaltic pump. This was one tough grape! None of the others we’d processed so far this season had behaved nearly in this way; not the Carignanes, not the Grenaches.

We got the flow going again, and later I made a trip through the fermentation hall. I reveled in the coolness and the comforting “glop, glop, glop” sound of grape slurry being fed into a big fermentation tank through a fat hose we call the anaconda. I climbed a ladder to a platform and poked my head inside the tank. “Mmmmh!” I exclaimed. So thick, so sweet!

Later that day, after lunch, I had a question for my boss.

“How old are your family’s País vines, really?” I asked him.

“Come,” he said, and led me to the tasting room. He motioned to an old map on the wall, which depicted the hacienda in 1861. This map had served as the last will and testament of his ancestor Don Estevan Manzanos Sola, indicating what he owned. It shows that the País we were processing that morning was in the ground at this time, which means these de-stemmer and hopper-clogging grapes had been planted no later than the mid-1800s. The vines are now nearly 200 years old.

And they’re going to keep on going. Fortunately, people around the world have begun to appreciate what País, version Century 21, is capable of. It is getting saved from extinction, and its full mature capability is being explored and admired.

País is indeed a pariah no more.

What is it like to drink?

“Easy. Not complex,” says my workmate Rodolfo.

That’s not exactly true in my opinion. País is certainly light-bodied, and rightfully lauded as being “quaffable”. It goes down smoothly and you can drink a lot of it without getting a headache. But it’s also distinctly delicious. Light and easy doesn’t necessarily translate to lacking in intensity.

More people around the world are now giving País a chance, and agreeing.

It’s true: Chilean País, the wine I am making right now with my own hands, has been listed by the glass in places as discerning as Manhattan’s Gramercy Tavern and London’s Annabel’s.

Way to go, People’s Grape!

Shy Devil

February 10, 2023

“Now I’ve done it,” I smiled, gazing into Quetrupillán’s caldera last Sunday, a hot summer day in Chile. “Twenty-eight years, one month, and twelve days after the fact.”

I’ve been engaging in some personal archaeology recently, a bit of private forensics, walking the summer volcanoes in Chile’s Lakes District and trying to piece together the puzzle of what happened to me here in 1994. In addition, I was on a mission: to finally walk the Villarica Traverse, which I missed out on all those years ago because of what happened.

It was high basin and snow walking all day, my journal entry reads from my camp on December 24, 1994. I felt good and strong all day, walking across those snowfields. I think I fried my face again. Getting lost was not a possibility.

Then I add: Next to me, above, is Quetrupillán, which I climbed today in a surreal mist…

“Really?” I asked myself now, twenty-eight Chilean summers later, as I gazed across the sunbaked moonscape. “Snowfields? Climbed Quetrupillán?”

Everything looked so unfamiliar that I almost doubted I’d ever been here in the first place. I had no recollection of the land being so parched, so dry. If not for the presence of my old friend Volcán Lanín looming behind me on the Argentine border, I’d have believed I’d never been here and dreamed the whole story up. Especially the climbing Quetrupillán part. That summit was just too far away, and there was no way I could have made a side jaunt to reach it. Getting there and back would have been a day’s expedition in itself.

I examined the vicinity and postulated which hill I’d actually climbed in “a surreal mist”, believing it to be Quetrupillán. I identified a candidate or two, and forgave myself for twenty-eight years of unintentional self-misrepresentation. Oh, the stories we tell ourselves!

“Well, there’s no time like the present,” I told myself now. Later that day I pitched my tent by the shore of Lago Patos Azules (Lake of the Blue Ducks, whom I met!), and spent the following day making the expedition to Quetrupillán.

“Now I’ve done you,” I smiled from the top, gazing into the caldera. “Now I know you, you Shy Devil.”

Which is what Quetrupillán means, or can mean, in Mapudungun. A literal translation of the name is “active volcano roaring”, but if you break it into two separate words, you get something entirely different. Quetru means “of few lights, timid,” and pillán is a term for a powerful, potentially malignant spirit.

Shy Devil.

I’ll take the latter explanation, because Quetrupillán is anything but active and roaring. Clearly it blew up big, once a very long time ago and decapitated itself. This was likely way before any humans were around to witness.