Six-Mile Disc

January 19, 2026

A curious feature appears when you view New Zealand from space. Within a lobe of the western coast of the North Island, a near-perfect circular disc of deep green jumps out at you, centered on a volcanic peak, backed by the paler green of surrounding farmland.

The volcano is Taranaki, now named Taranaki Maunga, formerly also known as Mount Egmont. At 2,518 meters (8,261 feet), it is the country’s second highest volcano. The deep green disc is old-growth forest that became protected way back in 1881, when the area within a six-mile radius of the summit was established as a forest preserve, and everything else got burned and cleared. In 1900 this disc became Egmont National Park, the country’s second national park. Much more recently, on April 1, 2025, the park’s name was changed to Te-Papa-Kura-o-Taranaki, and the mountain itself became a legal person. More on this in a moment.

The old-growth forest is utterly magical and mesmerizing, I can attest, having trekked 25 kilometers through it in a drizzle earlier this month (New Zealand being an affordable and accessible travel destination from home in Samoa). Never before had I experienced anything quite like this forest, and I got hypnotized in its vibe. Rich soil and lots of rain mean the whole region used to be like this; indeed, when Captain Cook visited in 1770 he noted a snow-capped peak with surroundings “clothed in wood and verdure.” Now all that remains of the verdure is the six-mile disc.

Outside the park boundary, what you see is intensive dairy farming. The region is home to about half a million milking cows; nearly 10% of the country’s herd cranks out its methane burps and other effluents here. Also present is the Fonterra’s Whareroa facility, the world’s largest milk ingredients factory by annual output, cranking out milk, milk powder, butter, casein, whey, and cheese. China is the number one export market.

The dairy thing is relatively new to New Zealand. When I first visited, in 1991, the reputation was still mostly about sheep. A common thing to say back then was that there were something like four sheep for every New Zealand person.

Cows, which are much harder on the environment, have since displaced sheep to a significant extent, to the degree that the country’s cow-to-person ratio is now nearly one-to-one. In the Taranaki Region, the ratio is more like five-to-one.

Dairy really got going here only after 1988, when damage from nearby-passing Cyclone Bola motivated many Taranaki farmers to switch from crops to cows. Then, in 2001, Parliament passed a dairy industry restructuring act which resulted in the two largest cooperatives merging with the New Zealand Dairy Board to create Fonterra, New Zealand’s largest company.

This is not to say that, had you seen the Taranaki Region from space 100 years ago, you wouldn’t have noticed the six-mile disc. Long before dairy, the slash and burn had commenced, and farms reached right up to the park boundary. A big boost happened back in 1865, when the colonizing government confiscated much of the region from local Māori people to provide farmland for military settlers.

I have a feeling what you expect me to do next: continue in language deeply reverential of the Māori and their eons-old connection with and stewardship of New Zealand’s natural world and each other, while summarizing atrocities of later-arriving Europeans. And this is exactly what I am not going to do.

Because that would be selective and creative storytelling that obscures and evades what actually happened. Throughout this trip to New Zealand, I noticed a pattern: a consistent slanting of the narrative, which skewed things Māori in a reverential light while being much more critical of other human beings.

I’ll give some examples below, but first let’s consider the time frame. You could be forgiven for supposing, based solely on the breadth and intricacy of Māori mythology, in which so many things are considered sacred, that the Māori have been in New Zealand for thousands of years. Of course, we know this is not true. The truth is that they arrived here a scant few hundred years prior to Europeans—a split second, essentially, in human history time frame terms. Within this very short period they did a lot of things, in addition to concocting an elaborate mythology.

Exact timing is still up to debate, but around the year 1300, people began arriving in canoes from much, much smaller islands in eastern Polynesia, ones that were necessarily resource-constrained, with all the warlike culture associated with scarcity deeply ingrained. New Zealand must have seemed utterly boundlessly bountiful to them at first, but within a half-dozen generations these people did what normal humans normally did and still do: formed tribes, burned forests, drove mass extinctions, and viciously fought each other over resources to the point of annihilation and genocide.

This information is well-established and very accessible to anyone who wants to study it to whatever level of detail. That’s not what I’m talking about here, when I criticize the narrative slant a person can casually receive while hanging out in modern New Zealand. What I’m talking about might best be illuminated by a few examples.

Take the moa, the legendary extinct, giant flightless birds of New Zealand, for example. Their forebears were present when New Zealand broke away from the Gondwana supercontinent eighty million years ago, and went on to survive at least thirty ice ages. Eleven species thrived at the time the first Polynesian canoe scraped sand, but they barely lasted for a hundred years after that, and were completely gone within two hundred years. It was one of the fastest extinctions in the history of the planet.

At the Moa Exhibit in the Taupo Museum, the placard mentions briefly that moa habitat was “diminished as Māori cut and burnt bush to plant crops and reduce surprise attacks from other tribes. The abundant bird life was a valuable food source and thus began the disintegration of many native species.” Then the text immediately pivots to the following spiel: Five hundred years later, Europeans arrived and continued to cut and burn the bush. They also drained the swamps and introduced possums, stoats, weasels, ferrets, rats, and hedgehogs. These predators faced no opposition or competition. Due to New Zealand’s isolation in the South Pacific, many birds had become ground dwellers, making them easy prey to the introduced species. The fight against these pests is far from over…

Huh? This is supposed to be the Moa Exhibit, talking about moa, which were gone shortly after the Māori arrived, before Europeans.

In other places, contradictions were jarring. Take the National Kiwi Hatchery outside of Rotorua for example (kiwi are nearly extinct in the wild, hence this hatchery). There, a placard reads, in large bold print at the top:

Māori have a special relationship with kiwi, in fact kiwi are a taonga (sacred) species. Traditionally, they are thought to be under the protection of Tāne Mahuta, god of the forest. As kiatiaki (guardians), Māori are protectors of our national icon.

Below, on the very same placard, in much smaller print, it reads:

Traditionally Māori hunted kiwi for meat, skin, and feathers. Dogs were sometimes used or nooses were set at the burrow entrances.

Hanging in the display case of this placard is a blanket made from kiwi feathers. “These cloaks aren’t just for everyone,” it advises. “They’re reserved only for chiefs” and said to carry the spirits of the birds they are “crafted from.”

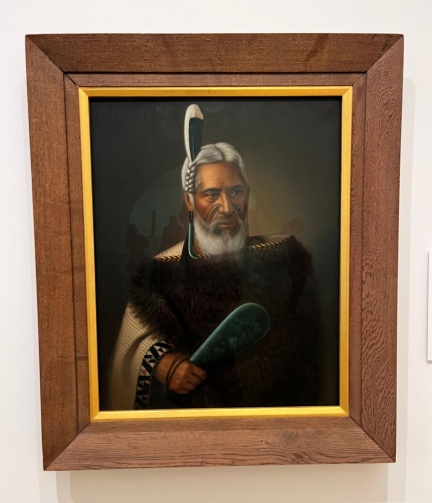

Speaking of dress, have you ever seen a picture of a Māori person in traditional dress, holding a paddle made of pounamu (jade), or other stone material? Repeatedly, in museum exhibits and in the two cultural shows we attended, we were told that such displays are ceremonial and respectful, symbolizing authority and status.

We were never told verbally, and only read in the fine print of museum exhibits, that the paddles were the lethal weapons of the Māori, the goal being to kill your opponent in close combat by going for the temple or juggler. Eventually men carried their paddles with them pretty much all of the time, even when taking a poo, because you never knew when an enemy would strike. Then the British came and introduced muskets, and the paddles, as weapons, went by the wayside. The Musket Wars of the 1800s ensued: a vicious cycle of Māori tribes purchasing muskets from the British in order to annihilate and enslave other Māori tribes, in order to plant more crops to sell to the British to buy more muskets.

Then there’s the abundant flowery language posted on signage in public spaces. Take this bit, from a café-qua-museum stop along the road to Cape Reinga (at the North Island’s northern tip), elaborating on wood used to make Māori canoes: Te Ara Whānui is our vision. It is the blueprint that sets a unified direction for the aspirations of Ngāti Kuri, underpinned by our history and the connections established by our ancestors…The name Te Ara Whānui refers to the many pathways of encounter that spread across the Far North. The pathways are drawn together by a waka (canoe)—a representation of our journey through time, and a reminder of the interconnection of all living things. The waka signifies the importance of our relationship and responsibilities to the natural world. It unifies and reminds us of the collective effort required to strengthen those elements that distinguish and determine our cultural identity and wellbeing.

What does that even mean?

Or this, from the top of a signboard at Aukland’s harbor: Te Ara Tukutuku is the Māori name used for waka (canoe) ramps to reflect how Māori used the original shoreline…It is also a metaphor for the binding of the land and sea—providing an elegant link between the domains of Tangaroa (the ocean) and Papatūānuku (Mother Earth)—and reflecting our vision for this space.

The signboard goes on to state, much less romantically, that in the past, the “entire precinct was utilized as a large scale fish processing plant. Waka were continuously dragged in and out of the water…The fish and sharks were scaled, gutted, and processed.”

Two days after hiking Taranaki, we did the Tongariro Crossing, a stunning 20-kilometer trek across the volcano complex south of Lake Taupo.

Of course, we were informed that we needed to stay on the trail at all times, not because it was the right thing to do, but because the surrounding lands were considered sacred. By then I was getting tired of hearing this. The word “sacred” had started to smell funny to me, especially when applied to the Earth’s landforms, by humans who had arrived a few hundred years before other humans. Of course I was going to stay on the trail. I didn’t need the word “sacred” to police me (and by the way, the act of walking on this Earth is sacred to me; I firmly believe it is our shared birthright). By now the word “sacred”, as applied here, smacked of the typical control, separation, and “power-over” humans are seeking when they invent and perpetrate religions.

Back to Mount Taranaki: it’s probably a good thing the Māori consider it sacred, else we might not have the Six-Mile Disc! In Māori lore the mountain, like all North Island volcanoes, used to reside in the center of the island. There, Taranaki and Tongariro battled for the love of Pihanga, another volcano. Taranaki lost and headed west, eventually becoming petrified in its current location. Tongariro’s periodic eruptions are a warning to Taranaki not to return.

You are allowed to climb Taranaki, and many do. But you aren’t supposed to walk to the highest point on the crater rim because that act is considered offensive by Māori.

You may have heard that, this past April 1, the Six-Mile Disc got a new name. It is now called Te Papa-Kura-o-Taranaki, which means “the highly regarded and treasured lands of Taranaki”. Also at this time, the mountain became vested as a legal person. I’m not sure what that means; Wikipedia says it means the park owns itself. I’m skeptical.

In other good news, the Six-Mile Disc became eradicated of goats in 2022, several years after getting free of pigs (which were introduced by the Māori) and deer. It still has possums, hares, stoats, weasels, and ferrets; more than a thousand traps are in place, and we saw quite a few of these traps alongside the trail.

Part of the goal is to rebuild the park’s kiwi population. Progress is being made!